This article was published in The Citizen Newspapaper on September 10, 2024.

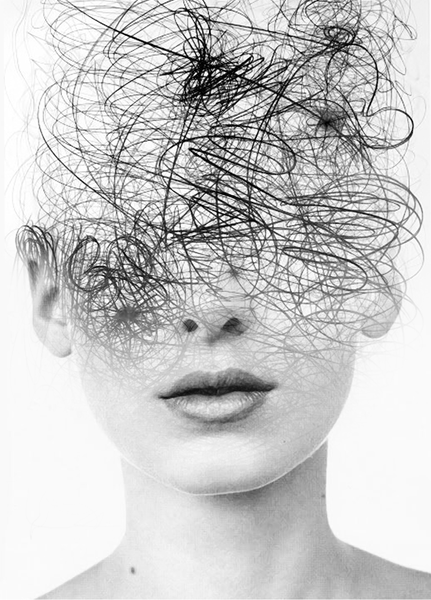

Beginning from a wider panoramic view, mental health has deep-rooted stigma across the African continent. Tanzania is not spared in this. While there is a rise in the public awareness of mental health now, there is still a lot to be done.

There are two aspects here, one is to end the segregation of those with noticeable mental illnesses or disabilities, and the other is to make people comfortable with accepting the reality when they really need mental health assistance. While no all mental health issues are clinical, but all need immediate professional handling to prevent escalation.

Mental health disorders is an umbrella term covering a variety of issues like: Depression, anxiety disorders, disruptive behaviour, dissocial disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders (behavioural and cognitive), eating disorders, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and others.

These disorders are much more common than we think. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) 1 in every 8 people globally lives with a mental disorder. WHO acknowledges the fact that most people do not have access to effective mental health care (WHO: Mental Disorders Fact Sheets, 2022).

Though many people are embarrassed with accepting having mental disorder, denial exacerbates the conditions, causing more disturbance in their thinking, behaviour and control/regulation of emotions.

However, while there is intentional denial which some use as a defensive mechanism, when unwilling to face the facts, there is also what experts call ‘anosognosia’ – a situation where one is unaware of their own mental health condition or they can’t perceive their condition accurately due to inaccurate insights.

Notwithstanding, due to partial negligence of the problem in most African countries over many years, it is hard to rely on available statistics which often differ across national and international research bodies.

In Tanzania for example, the first ever national mental health dialogue was held just recently in 2022.

We cannot compare our effectiveness in tackling this problem with countries like the United Kingdom where their first legislation concerning mental health was in 1774, called the Madhouse Act, and their first community mental health charity was launched in 1879, called ‘Together.’

They are certainly far ahead in diagnosis, community-oriented handling, as well as societal awareness on care of mental health patients. We are still at the low levels of breaking the stigma barrier and cancelling biases. Globally too it has been only 32 years since mental health was recognized as a global problem needing global solution.

In the 2011 Cross-Government mental health outcomes strategy for all people of all ages titled ‘No Health without Mental Health’, for example, the UK government identified mental health as a single largest cause of disability in the UK, contributing up to 22.8%, even more than cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

The economic costs put together include direct costs of services, lost productivity at work, and reduced quality of life. The cost of all that amounted to over 100 billion pounds each year, which was still deemed not sufficient.

In Tanzania just like other Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs), the budget allocation for mental health issues is significantly low.

A 2023 peer-reviewed research publication by Tanzanians Joel Ambikile and Masunga Iseselo, says: “Total mental health expenditure per person in the country is estimated to be Tanzanian Shillings 43.1. The government spends only 4% of the total government health expenditure on mental health. The country has 2 mental hospitals, 5 psychiatric units in general hospitals, one forensic inpatient unit, and 4 residential care facilities. The total number of the mental health workforce is 278 with rate per 100,000 populations being 0.06 for psychiatrists, 0.36 for mental health nurses, 0.01, for psychologists, 0.06 for social workers, and 0.02 for occupational therapists.” (Ref. Ambikile J.S. & Masunga I.K. in PLOS Global Public Health Journal, article no. 0001518, 2023).

Moreover, one problem we have not spoken about enough in Africa is associating mental health issues with witchcraft and superstition. Purely health and social problems are approached as spiritual problems, which further deviates from the line of proper treatment.

It is even worse when some kind of superstition and clairvoyance is involved, which oftentimes instigates hatred and conflicts within families, resulting in more complications.

Experts establish that mental health problems are not solely inherited. Their onset is a product of interaction amongst genetic, environmental and social factors.

The WHO particularly mentions among those at risk of developing mental disorders, those living in poverty, people with disabilities, and those who experience violence, disasters, and inequalities. These realities affect most people in our country today, and are far from being fully resolved.

While the government invests more in research, community based management structure and social health care services, it has also to be involved, with the help of interested organisations, in raising awareness and expose the existing stigma and the harm it causes so as to help safeguard lives. The citizens also need to be encouraged to seek professional mental health when the need is noticed, rather than denying, or even worse, entertaining superstition.